Every culture in the world is uniquely its own—each community possessing their own dialect, faith, expression, stories and histories. But the one thing they have in common, oftentimes predating organised language and communication skills, is music. From the Celtic chants of Scotland and the Calypso of the Caribbean to the folk music of India, every culture in the world has developed a distinctive musical style of their own, despite geographic barriers and topographical isolation. The universal phenomenon of music necessitates the investigation of the psyche of human beings, and what exactly it is in the wide human spectrum that gave birth to music. In other words, the psychology of music—the effect it has on a foetus, on memory and the hippocampus, in the centres of fear and arousal of our brain, as well as the ways it can be harnessed for providing therapy, are some of the concerns of music psychology.

Entering the Womb

The womb is a relatively quiet place, registering sounds from around 50-60 dB (the volume of normal conversation). The human foetus develops auditory organs in the sixteenth week after conception and can register sound by week 24. A newborn’s sense of hearing develops much faster than the other senses, suggesting that humans have a natural predisposition towards sound, with certain parts of the brain prioritising audio-triggered responses. In the late 1990’s, a phenomenon termed as the Mozart effect arose in society after popular media claimed that playing classical music to the baby bump would create intellectually superior individuals. While this theory has been disproved, modern research shows that playing music in the womb stimulates the mental activities of the baby to a great extent. For example, European researchers in 2013 found that exposing an unborn baby to music had a long-term effect on their brain. They discovered that newborn babies could remember a version of ‘Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star’ played to them in the womb and responded differently when alternate versions were played. These memories were created before they were born and lasted until the newborns were four months old.

There is concrete evidence to show that early development induced by musical stimuli will have a long lasting impact on the life of an individual. Studies have also shown that the genre of music affects the response of the unborn baby—after all, there’s a reason the Mozart Effect came into being. Classical music, lullabies and songs sung by the mother induce calmness and non-aggressiveness. However, loud music, hard rock, metal and rap, were seen to increase the rate of the baby’s heartbeat and trigger agitated movement within the womb.

Music and Memory

The documentary film Alive Inside (2014), follows social worker Dan Cohen who helped dementia patients by speaking to their families about the music they once enjoyed and compiling personalised playlists for them. The results of this experiment were extraordinary. Elderly patients who were unable to speak proceeded to dance or sing the lyrics. Some were able to recount when and where they had listened to the music. Music seemed to have unlocked certain doors to memory.

The hippocampus is a seahorse shaped structure present in the human brain, and has commonly been dubbed “the gateway to memory”, and for good reason. Not only is the hippocampus principally involved in storing long-term memories (LTM) and making those memories resistant to forgetting, it also helps in creating short term memories (STM) which are more likely to be passed onto the long-term memory. There is a very strong link between memory and music. The nature of music itself, with its repeating chords, rhythms, melodies, chorus and lyrics activates the STM while simultaneously creating LTM. This is the reason why we can remember a song we heard years ago on the radio, as well as recall the outfit we were wearing at the time, the people we were with, the emotions we felt.

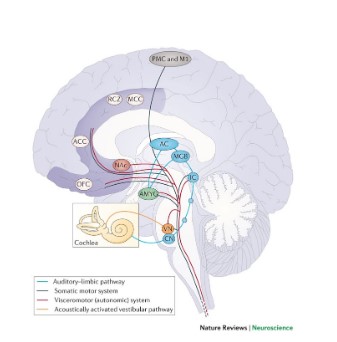

Evocating the Amygdala

Music stimulates many parts of the brain other than the hippocampus, most notably the amygdala—a small but crucial part of the limbic system. That primal rage you feel when the TV remote is snatched from your hand? Well, some part of it was induced in this emotional centre of the brain. The amygdala controls many feelings like joy, aggression, anxiety and curiosity. It’s heavily linked with the “fight or flight” instinct that we possess. It alerts us to negative stimuli like ambulance sirens or the barking of dogs as well as positive stimuli like a baby’s laughter or the ice cream truck. The amygdala’s connection to the brain is obvious—the responses to certain music genres are almost universal. Music can trigger those same emotional cues as the sounds mentioned above: a horror film soundtrack elicits an almost primitive fear, while a soaring battle march can create a surge of excitement.

In a similar manner, meditation music can soothe the mind in times of crisis. And an upbeat pop tune can bring an easy smile, regardless of the listener’s previous mood.

Evolutionary Musicology

Music is a fundamental part of our evolution; we probably sang before we spoke in grammatically guided sentences. Song is represented across animal worlds; birds and whales produce sounds, though not always melodic to our ears, but still rich in communicative functions. The creative capacity so inherent in music is uniquely human. Music itself has strong ties to motivation and social contact. Although only a small portion of people play instruments, most can sing or hum a tune, or at least are avid listeners. Music, to an extent, is all pervasive—like breathing. It’s present in human lives in some form or the other. The evolution of music allows for unique social expressions and strengthens connectedness.

Music Therapy

Music therapy finds its origin in Ancient Greece—the cradle of civilization—most notably in the writings of Plato and Aristotle. Even earlier records show ritualistic healings using chants and brass bells in South Asia. However, the first scientific studies of the effect of music on the well-being of humans began in the late 1700s. The earliest modern implementations of music therapy began in the aftermath of the destruction and chaos of World War II. Musicians in local pubs would perform for PTSD ridden veterans to raise their spirits and bring them hope. Surprisingly, the benefits of these performances were so noteworthy that doctors began to study the impact of music on mental health.

Music therapy is most effective when coupled with other practices like yoga, counselling and exercise, but it can be used independently without sacrificing results. Some implementations of music therapy includes:

- Reducing anxiety

- Provides relief to those patients suffering from Parkinson’s or Alziemer’s

- Reduces depression and loneliness

- Supporting the rehabilitation of disabled patients

- Building communication skills for children experiencing delayed development

The fundamental belief in this type of therapy is that music has the capability to alter the brain’s cognitive functions for the better. Therefore, music therapy forms an integral part of the study of music psychology, perhaps the most relevant in our times.

The evolution of man took a period of 30 million long years. As of the present moment, what makes us different from the other creatures of this planet is our ability to create.The power to synchronise vocal movements flexibly to an external pulse in order to create music is uniquely human. In simple cognitive terms, this ability separates us from animals. It would make music the decisive evolutionary step of the species Home sapiens.

The psychology of music, if it had to be broken down, is essentially the way the brain processes sound, how music affects the various parts of the brain, how music ties in with evolution, and music therapy. But the core of it all lies outside science as it exists now. Music can bring the same pleasure as primary drives like food, water or sex. Music can uplift us in dark times, it can be a lighthouse in the dreary sea of life. Therefore, understanding, studying and analysing music and the rich psychology behind it is vital.